By Martyn Walker

Published in Letters from a Nation in Decline

“Some crimes offend the law, others offend the senses. But a few — like dimming the sun — offend both, and then go on to threaten all life that depends on its light.”

— Laurence J. Peter, posthumously paraphrased

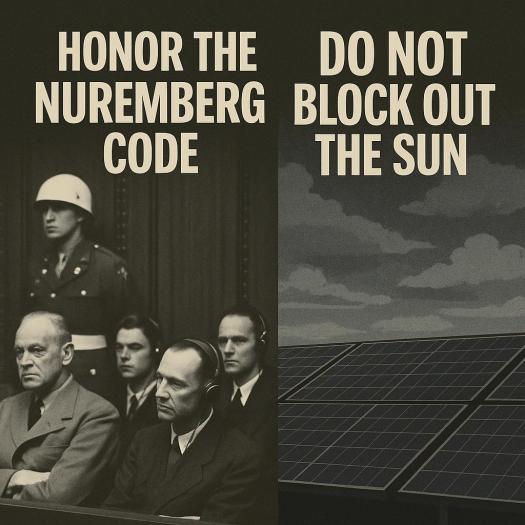

The Nuremberg Code Still Applies — Just Look Up

We are governed now by people who believe it is acceptable to experiment on the atmosphere — and by extension, on all life within it — without consent, oversight, or consequence. The proposal to “blot out the sun” under the guise of solar geoengineering may seem the stuff of science fiction, but it is not only real, it has been quietly sanctioned.

In this country, where grey skies already dominate the greater part of the year, the very idea that we should deliberately reduce sunlight warrants more than scientific scrutiny — it demands a reckoning with first principles.

Sunlight is not a pollutant. It is the original engine of life.

And yet, in the race to mitigate climate change, we are told that injecting particles into the stratosphere to reflect sunlight back into space might be necessary. The logic is simple, the risks profound. Reduce solar radiation, and you cool the Earth. But what else do you do?

You undercut solar panel yields, including those funded by government grants and individual savings alike. You suppress photosynthesis in farming regions, risking lower crop yields in a world already strained by food insecurity. You disrupt rainfall patterns, especially in equatorial and monsoonal zones. You reduce the availability of natural vitamin D, just as our GPs urge us to get more sunlight, not less.

You dim the world, literally and figuratively.

And all of it without a referendum. Without a vote. Without even a leaflet through the door.

Where is consent in this story? Where is accountability?

We are told that climate change is an existential threat, and perhaps it is. But that does not grant a government — or a consortium of scientists, or a supra-national fund — the right to conduct global-scale experiments with unknown long-term consequences, no matter how well intentioned. That is not precaution; that is hubris disguised as stewardship.

Which brings us — as all such questions eventually do — to the Nuremberg Code.

Drafted in the wake of war crimes and scientific atrocities, the Nuremberg Code was not simply a legal instrument. It was a moral declaration. It stated, for all time, that no human being should be subject to experimentation without their freely given, fully informed consent. No clever phrasing, no policy paper, no invocation of emergency, can supersede that.

While the Code was written for medical experimentation, its logic extends to any deliberate action that treats the population as passive subjects of a risk-laden intervention. If deploying sulphate aerosols in the stratosphere, or conducting atmospheric reflectivity trials, is not an experiment on all life — then what is it?

We must not allow ourselves to be softened into apathy by the presentation of these plans as purely scientific exercises. We must not forget that science, without ethics, becomes machinery in search of obedience. The ghost of the 20th century tells us plainly where that leads.

Consent must return to the centre of policy. Not only in medicine, but in environmental governance, data rights, digital identity, and energy strategy. To ignore consent in these spheres is not merely undemocratic — it is dangerous.

The great lie of the age is that we can offset our guilt, erase our emissions, or rebalance our planet with a few technocratic tweaks. But we are not gods. We are stewards, or we are fools. The choice is that stark.

And so, to those in government who sanction these sky-darkening schemes: remember the Nuremberg Code. Not because we seek prosecution, but because we believe you still have a conscience. Because shame, not fear, should stop you.

Because if not now, when?