How Power Learned to Hide in Plain Sight

By Martyn Walker

Published in Letters from a Nation in Decline

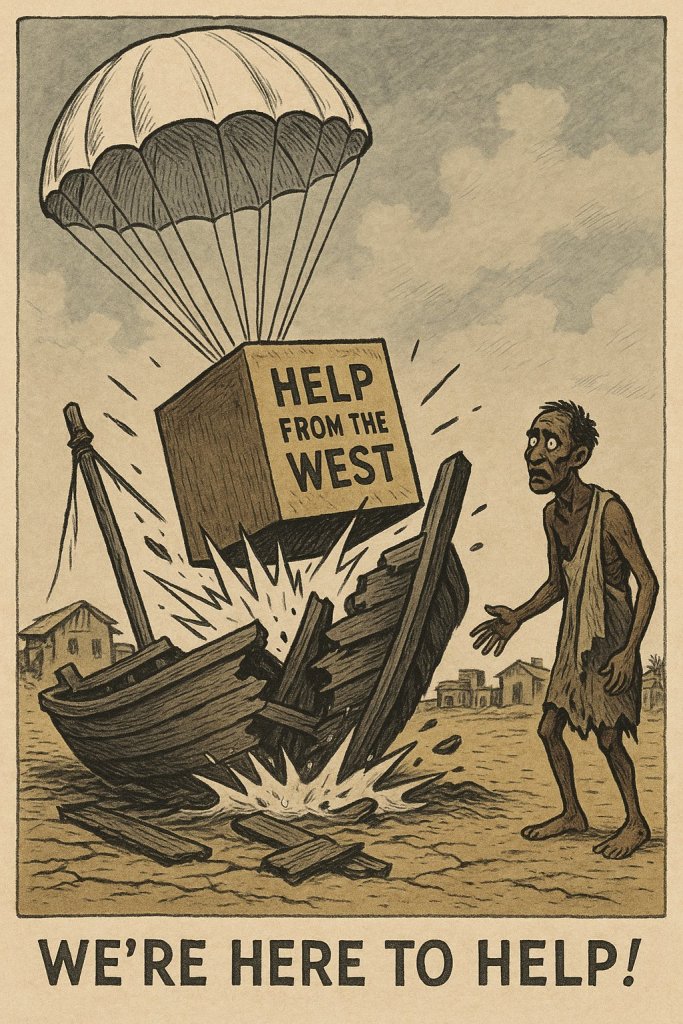

Nations do not collapse in spectacles of ruin. They decline administratively. The erosion of liberty rarely arrives with banners or barricades. It appears instead as guidance, optimisation, and protection, introduced through processes so mundane that resistance feels faintly unreasonable. The modern citizen is not ordered to surrender autonomy. He is persuaded to misplace it.

The evidence is seldom dramatic. It begins in trivial irritations: a device, purchased outright, quietly reconfigured by its manufacturer in the name of preservation. A setting deliberately chosen by the owner reappears in its default state following an update issued without consultation. The justification is rational, even defensible. The owner, it is implied, cannot be trusted to act in the best interests of his own property. The device must be protected from the individual who paid for it.

Such incidents would once have been regarded as impertinent. Today they are routine. Ownership has been replaced by conditional authorship. The citizen is permitted to configure his environment, provided he accepts that it will be periodically corrected by those who know better.

This transformation was not unforeseen. Early scholars of digital governance warned that authority would migrate most effectively when it ceased to rely upon legislation and embedded itself instead within technical architecture. Laws could be challenged, debated, and repealed. Systems, once operational, simply persisted. These thinkers argued that code would not merely enforce regulation but would become regulation — invisible, automatic, and resistant to democratic revision. They were regarded as imaginative theorists. Experience has quietly promoted their warnings into operational reality.

The same migration of authority is visible across British institutional life. The Post Office Horizon scandal demonstrated with exceptional clarity how technological infallibility, once declared, can displace both justice and reason. Hundreds of sub-postmasters were prosecuted, bankrupted, and socially destroyed because an institution found it easier to criminalise human testimony than to question the reliability of its own system. The tragedy was not simply technological failure. It was administrative certainty. The machine could not be wrong because the institution could not afford for it to be wrong. Authority defended software and prosecuted citizens.

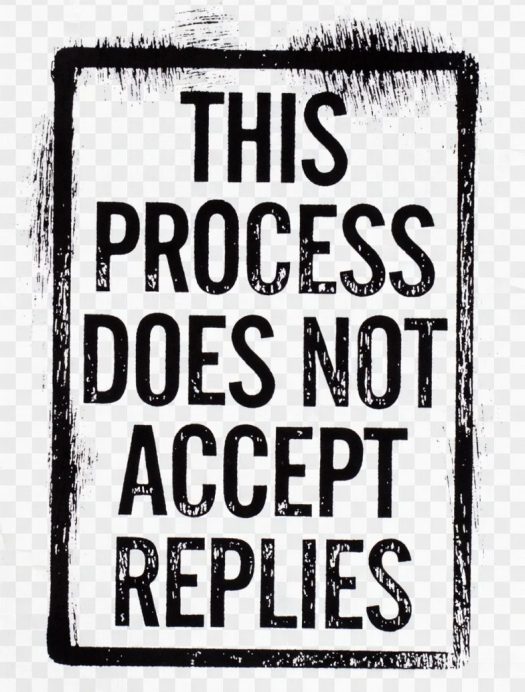

The lesson was received with remarkable efficiency, though not in the manner one might have hoped. Banking, once an archetype of reciprocal commercial trust, has undergone a similar evolution. Open banking and strong customer authentication were introduced under the language of empowerment and security. In practice, they have entrenched a regime in which access to one’s own finances requires continuous verification, behavioural monitoring, and tolerance of persistent inconvenience. Banks contact customers urgently when information is required, typically through messages that cannot be answered. When customers require assistance, they encounter automated barriers, rationed human contact, and communication channels designed less for dialogue than for containment.

The commercial asymmetry would be remarkable if it were not now so familiar. Customers deposit capital, entrust personal data, and assume institutional risk, yet must compete for access to services they themselves finance. Increasing numbers have responded with understated pragmatism by withdrawing funds and transferring them to organisations still willing to communicate through email, telephone, or direct messaging. Traditional banks appear increasingly content to retreat from service provision and reconstitute themselves as regulated custodians of trust, extracting revenue from payment infrastructure while ceding innovation to more agile intermediaries.

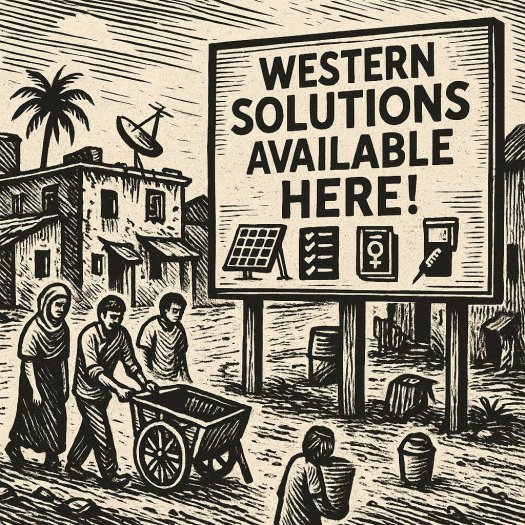

Energy policy provides an equally instructive example. The smart meter rollout was presented as an instrument of transparency, enabling consumers to monitor consumption and reduce costs. In reality, it created a technological platform capable not merely of measurement but of behavioural enforcement. Pricing, usage, and consumption patterns increasingly fall within the administrative discretion of infrastructure operators rather than household decision-makers. The consumer is encouraged to regard this transfer of authority as environmental virtue. Choice remains available, but only within parameters determined by those insulated from the consequences of their decisions.

Speech, once regarded as the cornerstone of democratic legitimacy, has been subjected to similar administrative refinement. The Online Safety Act establishes a regulatory framework in which lawful expression may nonetheless be suppressed through platform enforcement incentives. Companies are encouraged to remove content pre-emptively, not because the law demands such caution explicitly, but because regulatory penalties reward over-compliance and punish hesitation. Authority is exercised indirectly, through incentive structures that render dissent economically hazardous rather than legally prohibited.

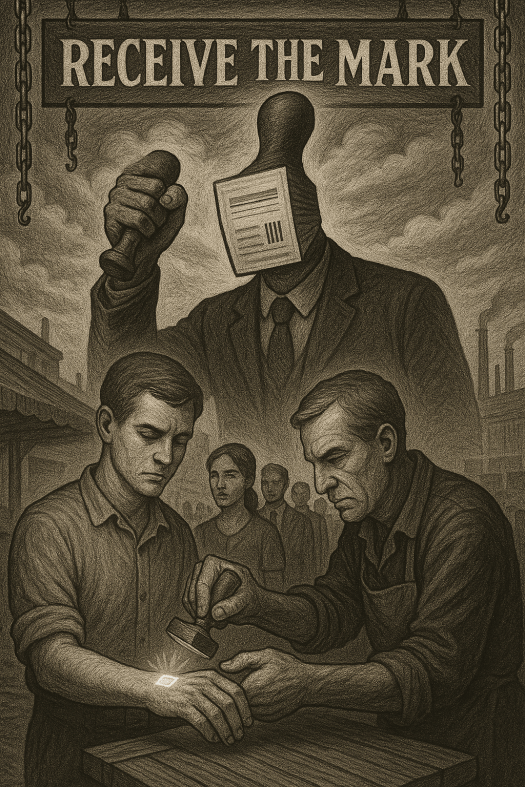

What unites these developments is not ideology but method. Authority has ceased to argue and begun to embed. Political choices are recast as technical necessities. Opposition is reframed as misunderstanding. Compliance becomes the default condition of participation in modern society.

British legal tradition once contained formidable defences against such encroachments. The common law principle that a man’s home is his castle expressed more than property rights; it embodied a presumption of personal sovereignty. The doctrine of administrative reasonableness required state decisions to withstand rational scrutiny. These traditions assumed that authority required justification and that power, to remain legitimate, must remain visible. Contemporary governance increasingly operates through mechanisms that evade these safeguards by translating decisions into technical processes and automated compliance frameworks. Authority is no longer asserted. It is compiled.

The genius of this transformation lies in its civility. No one is dragged from his home for criticising a regulatory regime. Instead, his account is restricted. His transactions are delayed. His content is deprioritised. His choices narrow quietly until dissent becomes administratively exhausting. Coercion is replaced by friction. Consent is replaced by fatigue.

The modern bank exemplifies this evolution. Once sustained by personal relationships and local accountability, it now survives primarily as a certified intermediary between the citizen and financial infrastructure. Trust, formerly cultivated through accessibility and service, is increasingly reduced to regulatory compliance and institutional branding. Payments, lending, and savings services are steadily migrating to technologically agile platforms. The bank’s remaining utility lies in its authority to validate identity and satisfy regulatory expectation. It becomes less a merchant and more a notary.

The small acts of resistance that persist — closing accounts, disabling unwanted functions, declining digital credentials — acquire symbolic significance precisely because their practical impact is limited. They represent attempts to preserve authorship within systems designed to reduce the citizen to a user. They recall an older constitutional settlement in which instructions, once given, remained in force until deliberately changed.

But symbolism cannot substitute for structure. A society that relies upon individual vigilance to preserve autonomy has already conceded the principle of autonomy. Freedom that survives only through constant technical alertness is freedom in retreat.

The transformation of authority into architecture carries one further and rarely acknowledged consequence. When power embeds itself within systems, it becomes insulated not only from public debate but from moral responsibility. Decisions appear as outcomes rather than choices. Accountability dissolves into process. The citizen is left negotiating with interfaces rather than institutions.

It may yet be that none of this is malicious. Indeed, it is far more unsettling if it is not. A society that relinquishes autonomy not through oppression but through administrative convenience demonstrates a subtler and more permanent form of decline. When citizens grow accustomed to being managed rather than represented, corrected rather than persuaded, and optimised rather than trusted, they cease to notice the distinction between governance and supervision. By the time they do, if they do, they will discover that the mechanisms designed to protect them from inconvenience have succeeded only in protecting power from accountability. Nations rarely lose their freedoms in a moment of catastrophe. They misplace them gradually, misfiled among compliance procedures, customer journeys, and software updates that nobody remembers requesting.

Afterword

By Laurence J. Peter (Posthumously, and With Considerable Relief That He Cannot Be Blamed for Any of This)

The study of bureaucratic expansion demonstrates that institutions rise to meet the limits of their competence and then continue rising with admirable indifference to gravity. In previous centuries, this phenomenon expressed itself through memoranda, filing cabinets, and committees convened to explain why earlier committees had failed to produce sufficient memoranda. Modern technology has improved the efficiency of this process while preserving its essential spirit.

One should never underestimate the capacity of a system to protect itself from the inconvenience of the public. The moment a service becomes essential, its providers begin the delicate transition from assistance to administration. This transformation is achieved not through declaration but through refinement. Procedures multiply. Access narrows. Compliance acquires moral overtones.

Several governing principles may be observed. Institutions invariably mistake longevity for legitimacy. Any organisation that describes itself as customer-focused has already redirected its focus elsewhere. The more a system promises frictionless interaction, the more elaborate its hidden mechanisms of friction become. Technology does not eliminate bureaucracy; it digitises it, accelerates it, and renders it permanently accessible.

When an institution assures the public that it acts for their safety, the prudent observer determines whose safety is under discussion. Access that can be granted can be withdrawn with admirable administrative efficiency. Trust transferred from personal relationship to institutional certification becomes indistinguishable from compliance. Citizens repeatedly required to confirm their identity eventually begin to doubt its permanence.

Processes described as streamlined have typically removed the element that permitted dissent. Efficiency, pursued as a moral objective rather than a practical one, produces systems that function flawlessly for everyone except their users. Incompetence rarely destroys institutions. It reorganises them. Failure, sufficiently systematised, becomes policy. Policy, sufficiently complex, becomes immune to reform. Reform, sufficiently delayed, becomes heritage.

The citizen confronting this landscape is advised to cultivate a modest but persistent scepticism toward any authority that offers convenience in exchange for discretion. He should distrust the large promises, read the small print, and retain, wherever possible, the habit of asking why. This will not prevent decline, but it may delay its paperwork.

References

• Post Office Horizon IT Inquiry, Final and Interim Reports, UK Statutory Public Inquiry chaired by Sir Wyn Williams, 2020–present

• House of Commons Business and Trade Committee, Post Office and Horizon IT Inquiry Evidence Sessions and Reports, 2022–2024

• European Union Revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2), Directive (EU) 2015/2366 on payment services in the internal market

• UK Open Banking Implementation Entity, Open Banking Standards and Framework Documentation, mandated by the Competition and Markets Authority following the Retail Banking Market Investigation Order 2017

• Competition and Markets Authority, Retail Banking Market Investigation Final Report, 2016

• Financial Conduct Authority, Strong Customer Authentication and Secure Communication under PSD2, Regulatory Technical Standards and FCA Guidance, 2019 onwards

• National Audit Office, Rolling Out Smart Meters, HC 12 Session 2018–2019

• Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, Smart Meter Implementation Programme Annual Reports, various years

• UK Parliament, Online Safety Act 2023, c. 50

• Ofcom, Online Safety Regulation Framework and Risk Assessment Guidance, 2023–2025

• Associated Provincial Picture Houses Ltd v Wednesbury Corporation [1948] 1 KB 223, establishing the Wednesbury principle of administrative reasonableness

• Semayne’s Case (1604) 5 Co Rep 91a, foundational common law authority for the doctrine that a person’s home is their castle

• Dicey, A. V., Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution, first published 1885, for classical articulation of rule of law and limits on administrative authority

• House of Lords Constitution Committee, The Legislative Process: The Delegation of Powers, HL Paper 225, 2017–2018

• National Cyber Security Centre, Guidance on Secure Customer Authentication and Fraud Prevention, supporting regulatory approaches to digital identity and verification

• UK Government, Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, UK Digital Identity and Attributes Trust Framework, updated editions 2022–2024

• House of Commons Public Accounts Committee, Smart Meter Rollout Progress Reports, various sessions 2018–2024

• Bank of England and HM Treasury, The Digital Pound Consultation Paper, 2023, discussing centralisation of payment infrastructures and identity verification implications

• Zuboff, Shoshana, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, 2019, widely cited academic work on behavioural data control and digital governance trends

• Lessig, Lawrence, Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace, 1999 (and Version 2.0, 2006), foundational theory on technological architecture as regulatory authority