By Martyn Walker

Published in Letters from a Nation in Decline

When the state plans to dim the sun while blanketing farmland with solar panels, only folly thrives.

I installed solar panels some years ago. A modest gesture, perhaps, but one rooted in the belief that renewable energy—particularly the power of the sun—offered a sensible path forward. The promise was straightforward: invest now, harvest the sun’s rays, lower my bills, and contribute, in some small way, to a greener future.

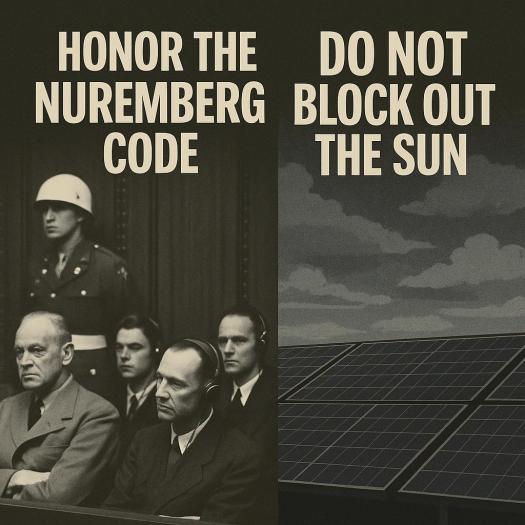

Imagine, then, my reaction upon learning that the government is now considering blotting out the sun.

I do not exaggerate. At Westminster, serious people are discussing the allocation of billions to solar geoengineering—spraying fine particulates into the atmosphere to reflect sunlight away from the Earth, cooling the planet in the process. Sulphur dioxide is the preferred agent, mimicking the effect of volcanic eruptions, lowering global temperatures, and, we are told, sparing us from climate catastrophe.

At the same time, those same serious people are approving hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland for conversion into solar farms. Arable fields, once the source of our food, will be turned into glinting expanses of silicon and glass—desperate to capture the very sunlight the state proposes to dim.

Which is it? Are we to harvest the sun or hide from it?

This is policy schizophrenia at its finest. On one hand, we are to bow before the gods of net zero, covering our green and pleasant land with solar panels. On the other, we are to fund atmospheric experiments that will diminish the very light those panels need to function. The left hand builds; the right hand dismantles.

But this is more than a contradiction. It is the arrogance of central planning, an affliction that has toppled empires, destroyed livelihoods, and now threatens to snuff out the sun’s warming rays.

History is not short of warnings. In the Soviet Union, one Trofim Lysenko convinced Stalin that science itself could be bent to ideology. Genetics was bourgeois nonsense, he claimed, and crops could be trained—like loyal Party members—to thrive in hostile environments if only they were exposed to the correct conditioning. Real scientists, those who objected, were purged. Their warnings ignored. The result? Agricultural collapse, famine, and death on an industrial scale.

The lesson? When policy bends science to ideology, crops fail and people starve.

Geoengineering smells of the same hubris. The climate models, neat as they are, do not account for the complex choreography of atmosphere, ocean, and biosphere. The Earth is not a thermostat, waiting for a bureaucrat to dial in the desired temperature. There is no slider bar for unintended consequences.

Consider CFCs—chlorofluorocarbons. Once hailed as a miracle of modern chemistry, powering refrigeration, aerosols, and industrial processes. Until, decades later, scientists discovered they were quietly eating away at the ozone layer, exposing us to dangerous levels of ultraviolet radiation. It took an extraordinary global effort—the Montreal Protocol—to halt the damage. The unintended consequence of human ingenuity.

Now, we propose to tamper with the atmosphere once again. To spray particles into the sky, with only the faintest grasp of what might follow. Droughts in one region, floods in another. Failed harvests. Shifts in monsoon patterns. The arrogance of assuming we can control a global system as intricate as the climate without consequence is staggering.

And all this while tearing up farmland to make way for solar panels, sacrificing food security for energy generation, only to dim the light that powers them.

It is the insanity of the moment, yes—but also the failure to learn from history. Grand schemes, unmoored from reality, sold on visions of salvation but delivered through wreckage and regret.

The late pathologist’s words echo: Humans are tropical creatures. Leave a man naked outside at 20°C, and he will die from exposure. We are built for warmth, for sunlight. The sun is not our enemy. It is our origin.

This is a nation in decline: dimming the sun, sterilising the soil, trading common sense for ideology. No thought for consequence. No humility before the complexity of life.

I do not ask for much. Protect the farmland. Let the sun shine. Reject the delusion that we can reorder the heavens by committee. We are not gods, and this is not our playground.

When the crops fail and the skies darken, there will be no bureaucrat to blame but ourselves.

🔬 UK Government Initiatives on Solar Geoengineering

- UK Scientists to Launch Outdoor Geoengineering Experiments

The Guardian reports on the UK’s £50 million funding for small-scale outdoor experiments aimed at testing solar radiation management techniques, such as cloud brightening and aerosol injections. Critics express concerns about potential environmental risks and the diversion from emission reduction efforts. (UK scientists to launch outdoor geoengineering experiments)

- Exploring Climate Cooling Programme

An overview of the UK’s climate engineering research initiative, detailing the government’s £61 million investment in solar radiation management research, including methods like stratospheric aerosol injection and marine cloud brightening. (Exploring Climate Cooling Programme)

- The UK’s Gamble on Solar Geoengineering is Like Using Aspirin for Cancer

A critical opinion piece likening the UK’s investment in solar geoengineering to treating cancer with aspirin, highlighting the potential dangers and ineffectiveness of such approaches in addressing the root causes of climate change. (The UK’s gamble on solar geoengineering is like using aspirin for cancer)

🌾 Solar Farms and Agricultural Land Use

- Super-Sized Farms or Rooftop Panels? The New Divisions Over Solar

The Times discusses the growing tensions between large-scale solar farm developments on agricultural land and the push for rooftop solar installations, emphasizing the need for balanced energy strategies that consider food security and community impact. (Super-sized farms or rooftop panels? The new divisions over solar)

- Solar Farms v People Power: The Locals Fighting for Their County

The Guardian highlights local opposition to massive solar farm projects in Norfolk, illustrating the conflict between renewable energy goals and preserving rural landscapes and livelihoods. (Landowners cover countryside with solar panels in ‘sunrush’)

- Factcheck: Is Solar Power a ‘Threat’ to UK Farmland?

Carbon Brief examines claims about solar farms posing threats to UK farmland, analyzing data and policies to assess the actual impact on agricultural land use. (Factcheck: Is solar power a ‘threat’ to UK farmland? – Carbon Brief)

🗣️ Critical Perspectives and Policy Analysis

- Why UK Scientists Are Trying to Dim the Sun

The Week provides an overview of the UK’s funding for controversial geoengineering techniques, exploring the scientific rationale and the ethical debates surrounding these interventions. (Why UK scientists are trying to dim the Sun | The Week)

- Analysis: Plans to Cool the Earth by Blocking Sunlight Are Gaining Momentum but Critical Voices Risk Being Sidelined

UCL’s analysis warns of the rapid advancement of solar geoengineering research without adequate consideration of dissenting opinions and the potential for self-regulation leading to dangerous outcomes. (Analysis: Plans to cool the Earth by blocking sunlight are gaining …)

- Solar Geoengineering Not a ‘Sensible Rescue Plan’, Say Scientists

Imperial College London reports on a study indicating that reflecting solar energy back to space could cause more problems than it solves, questioning the viability of solar geoengineering as a climate solution. (Solar geoengineering not a ‘sensible rescue plan’, say scientists)

Metadata

Letter Number: XIII

Title: Blotting Out the Sun

Collection: Letters from a Nation in Decline

Author: Martyn Walker

Date: 28 April 2025

Word Count: 1,210

BISAC Subject Headings

POL044000: Political Science / Public Policy / Environmental Policy

SCI026000: Science / Environmental Science (incl. Climate Change)

TEC031010: Technology & Engineering / Power Resources / Solar

BUS032000: Business & Economics / Infrastructure

SOC055000: Social Science / Agriculture & Food Security

SCI092000: Science / Ethics (incl. Environmental Ethics)

Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH)

Solar Energy—Government Policy—Great Britain

Geoengineering—Environmental Aspects—Great Britain

Agriculture and Energy—Great Britain

Central Planning—Political Aspects—Great Britain

Environmental Policy—Moral and Ethical Aspects

Food Security—Great Britain

Climatic Changes—Moral and Ethical Aspects