On the UN’s SDGs, Western Paternalism, and the Commodification of Virtue

By Martyn Walker

Published in Letters from a Nation in Decline

Dear Reader,

There was a time when the phrase international development conjured images of progress: clean water flowing from a new pump, a smiling child with a textbook, solar panels glinting on a school roof. Today, it increasingly conjures something else: a Western official in a tailored linen suit, lecturing villagers about climate obligations while their nation’s lithium is quietly sold to Tesla and their diesel generators are shut off.

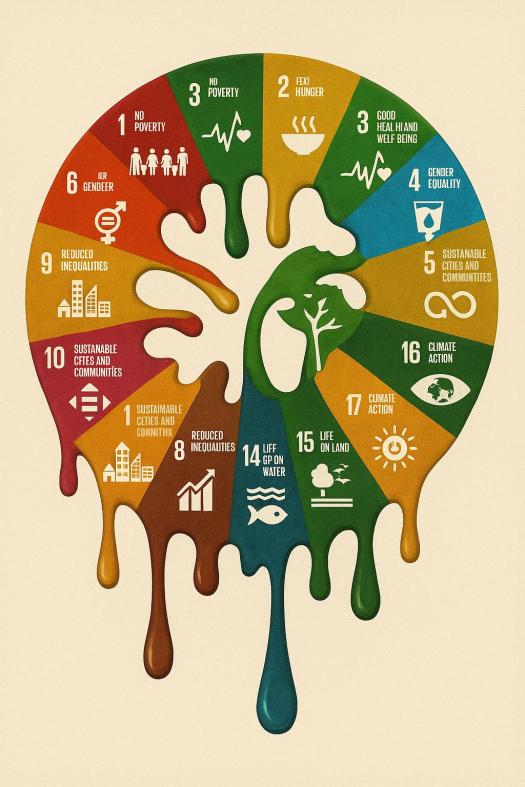

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals—17 of them, each with bullet points and colourful infographics—were meant to herald a new global era. Eradicating poverty. Ending hunger. Empowering women. Who could object?

But slogans are easy. It is the method of implementation, and the selective blindness, that reveal the deeper truth.

The Good

Let us not be unfair. In isolation, many SDG-aligned initiatives have brought tangible benefits. Literacy has risen. Infant mortality has dropped. Boreholes and mobile money have transformed some communities. Life expectancy in many African nations has improved dramatically since the 1990s. We’ve seen school feeding programmes that allowed girls to attend school for the first time. We’ve seen solar panels providing basic electricity where the grid never reached.

But we cannot mistake these successes—often born of local grit and ingenuity—for the triumph of global strategy. The SDGs were not the cause of progress. They became its branding.

The Bad

A closer look reveals a dismal pattern: Western governments, corporations, and NGOs deploy the SDGs not as a framework for empowerment but as an operating licence—a pretext for influence and control.

- African nations are told they cannot use their own fossil fuel reserves, lest they “violate SDG 13,” while Europe quietly returns to coal.

- Development banks, citing SDG “clean energy targets,” refuse to fund gas power plants in Nigeria or Mozambique—countries rich in natural gas and desperate for reliable electricity.

- In the name of SDG 12 (responsible consumption), African textile industries are wiped out by bales of cast-off clothes from Britain, Germany, and the US.

- SDG 5 (gender equality) becomes an excuse to impose Western cultural standards with zero regard for local context, alienating both men and women.

Even the roads, ports, and railways built under SDG 9 are often financed by foreign loans, constructed by foreign firms, and designed to facilitate resource extraction, not local resilience.

The Ugly

Worse still is the moral posturing. The SDGs have become an ethical fig leaf for what is, at heart, a continuation of imperial economics by other means. The tools have changed—no more Maxim guns and map lines—but the outcomes are familiar:

- Raw materials flow out.

- Debt, directives, and donor strings flow in.

- Lectures are delivered about “transparency” by those who launder African wealth into London property.

A friend in Kenya recently sent me a photograph—a cardboard sign arguing that fossil fuels are essential to achieving the SDGs, not an obstacle. He is not alone. In Ghana, Senegal, Uganda, there is growing anger that while Western nations enriched themselves through coal, oil, and gas, Africans are now told to leapfrog into solar-powered sewing machines and skip the very industries that built Britain, Germany, and the United States.

They are told they must save the planet. A planet they did not ruin.

And if they object? If their leaders push for resource nationalism or challenge the green dogma? They are punished with bad credit ratings, NGO campaigns, and trade restrictions dressed up as ethics.

“We were told to dream with the SDGs, but woke up in a minefield. They promised us progress, gave us guidelines, then took our resources and told us to be grateful.”

A Personal Turning Point

I was turned against the UN quite a few years ago when I read the transcript of a debate revealing the UN’s outrage that Google did not give UN-backed reports extra weight over non-UN ones—particularly on climate. The irony? Even their own climate scientists had expressed doubts about the overblown rhetoric spewing from the political wing. Shortly thereafter, those inconvenient internal criticisms all but vanished from search results. That was the moment many of us, curious about the truth, heard the alarm bells.

But it didn’t stop there.

What sealed my opinion was not some subtle drift into ideological territory, but the sheer absurdity of its pronouncements. Perhaps the most comical—and simultaneously tragic—example was the moment the UN Secretary-General stood in front of a global audience, announcing with a sanctimonious glare that:

“The oceans are boiling.”

He said it with the air of a pope issuing doctrine—daring anyone to challenge such claptrap. That was the day they lost even the illusion of dignity. That was the day they started believing their own lies.

At the time, I didn’t think much more of it. Like most citizens, I didn’t really know what the UN was, how it was funded, or why it existed in its current form. But since then, I’ve read more. And while I still wholeheartedly approve of the idea of the UN—born from the wreckage of world war, with noble intent—I now wholeheartedly disapprove of its continued existence in this form.

It needs to be dismantled, and rebuilt for the modern age. And crucially, it must come with a known expiry date.

There needs to be a regular renaissance in such powerful institutions. It must be written into their articles of association that they do not exist in perpetuity. That every few generations, they are dissolved, reviewed, restructured, or replaced—by those who live with the consequences of their actions, not those who fund their inertia.

Only then can future generations repair the damage of the past.

Britain’s Role in the Decline

Britain once led the world in infrastructure, finance, and engineering. Today, we lead in hypocrisy.

- We pressure African governments to abandon hydrocarbons while issuing new oil licences in the North Sea.

- We demand their “transparency” while our banks hold the stolen proceeds of their corruption.

- We celebrate our aid budget, yet make it near impossible for African students, scientists, or entrepreneurs to obtain a visa.

We mouth platitudes about “shared prosperity” while making damn sure the terms are written in our favour.

Even our charities—once a source of soft power—now act like minor UN agencies, full of slogans and interns and not much else. Oxfam lectures on social justice from offices built with funds extracted from taxpayer-backed contracts in countries they claim to help.

What Comes Next?

If the SDGs were sincere, they would prioritise energy sovereignty, industrialisation, and fair terms of trade. They would acknowledge that wealth must be created, not merely redistributed. They would empower Africans to determine their own path, even if that path includes diesel trucks, natural gas, and industrial-scale fertiliser.

Instead, they’ve become a system of moral accounting where Western nations get to “offset” their consumption by dictating how others should live. Carbon credits replace common sense. ESG ratings trump economic growth. And development becomes something done to Africa, not with it.

Final Words

The tragedy of the SDGs is not just that they fail. It is that they pretend to succeed, while preserving the very inequalities they claim to abolish. They are the smiling mask of a system that would rather fund a water kiosk than allow Africa to build its own water companies.

So let us end the deceit.

The real goal is not sustainable development.

It is sustainable dependence.

And unless we say so clearly, unapologetically, and publicly, we will continue to be complicit in dressing up domination as partnership—while another generation of Africans is told they must wait, suffer, and obey for the good of the planet.

Let the record show: it wasn’t just the empire that failed Africa.

It was the ideology that replaced it.

Beneath the Halo: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of the 17 SDGs

They came dressed as salvation, wrapped in coloured icons and global applause. But beneath the graphics lies a mess of contradictions, compromises, and collateral damage. Here we unpack each goal—not as it was dreamed up in Geneva, but as it has landed on the ground.

SDG 1: No Poverty

The Good: Billions in aid and NGO projects have lifted individuals out of extreme poverty zones temporarily; mobile banking and microcredit schemes have shown promise.

The Bad: Aid dependence fosters inertia, bypasses national institutions, and undermines local agency. Most African nations are still net exporters of capital due to debt servicing.

The Ugly: Western corporations extract billions in raw materials while pontificating about “inclusive growth.” Poverty statistics improve, but wealth inequality worsens. The SDG becomes a photo-op for billionaires with private jets.

SDG 2: Zero Hunger

The Good: Targeted food programmes, agricultural support, and school meal initiatives have helped reduce childhood hunger in some regions.

The Bad: African farmers often sidelined by subsidised Western food imports, distorting markets. GMO push disguised as philanthropy.

The Ugly: Western companies extract palm oil, cocoa, and coffee from African soil while Africa imports wheat and rice from abroad. The hunger remains—homegrown solutions are discouraged or sabotaged.

SDG 3: Good Health and Well-being

The Good: Vaccination campaigns and anti-malaria nets have saved lives. International coordination during outbreaks like Ebola did have positive effects.

The Bad: Health systems remain donor-dependent and brittle. Drug patents and pharmaceutical monopolies keep treatments unaffordable.

The Ugly: The West lectures on population control while funding sterilisation clinics, not hospitals. During COVID, African nations were last in line for vaccines—after being blamed for variants they didn’t cause.

SDG 4: Quality Education

The Good: Literacy rates have risen. Girls’ access to education has improved in measurable ways. Donor-led digital education pilots show promise.

The Bad: Much curriculum remains colonial, prioritising Western languages and values. Local history, trades, and culture are neglected.

The Ugly: Elites send their children abroad while rural schools lack desks. The promise of education is often betrayed by a total lack of post-education opportunity—thus fuelling migration.

SDG 5: Gender Equality

The Good: Gender-based violence laws have improved; access to reproductive healthcare and rights is more prominent in policy.

The Bad: Western ideologies about gender are imposed wholesale, clashing with cultural contexts and often backfiring. Tokenism abounds.

The Ugly: Gender NGOs become tools for regime manipulation—undermining families and traditional structures without offering durable alternatives. Men are alienated and women overburdened.

SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation

The Good: Boreholes, sanitation drives, and community projects have improved access. Urban water utilities have seen improvements in some cities.

The Bad: Infrastructure aid often bypasses local contractors, leaving no skills behind. Many projects fall apart when donor support ends.

The Ugly: The West donates filtration kits while Coca-Cola and Nestlé extract billions of litres of water from African aquifers tax-free.

SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

The Good: Solar microgrids and off-grid solutions have brought lighting and phone charging to rural communities.

The Bad: Energy poverty still affects over 600 million Africans. Fossil fuel investment is blocked by Western ESG policy, even while Europe reopens coal plants.

The Ugly: Africans are told to skip fossil fuels and use wind and solar, while the minerals to build those systems are mined from Africa under exploitative conditions.

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth

The Good: Youth employment schemes, support for entrepreneurship, and digital microbusiness infrastructure (e.g. mobile money) have opened doors.

The Bad: Most “growth” is in extractive sectors or the informal economy—precarious, low-paid, and unsustainable. Western firms set the wages.

The Ugly: Africa exports raw materials, imports finished goods, and is then scolded for not being productive. “Decent work” rarely applies to cobalt miners, plantation labourers, or garment workers sewing for Western brands.

SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

The Good: Roads, ports, and telecoms have expanded. Some African nations are incubating home-grown tech hubs.

The Bad: Most large infrastructure is debt-financed, often by China, and subject to foreign engineering, foreign profit, and foreign interests.

The Ugly: The West blocks industrial policy under free-market ideology, then tells Africa to “innovate” without fossil fuels, railways, or steelworks. Sovereign development banks are discouraged; dependency is institutionalised.

SDG 10: Reduced Inequality

The Good: Domestic reforms and global awareness of inequality have gained traction; some inclusive finance models have shown local promise.

The Bad: Inequality between nations is widening, not shrinking. Aid is given with one hand and taken back with interest payments.

The Ugly: The richest 1% are mostly Western, and mostly preaching equity to the poorest 10%—while African minerals fund their electric vehicles. The hypocrisy is baked in.

SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities

The Good: Investment in resilient urban planning, public transport systems, and affordable housing is theoretically rising.

The Bad: Urban sprawl without services defines most African megacities. Informal settlements are bulldozed in the name of sustainability.

The Ugly: Climate finance is used to displace communities in favour of eco-projects no one asked for. Slums grow, while the reports boast of “smart city frameworks” and pilot zones built for Western investors.

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production

The Good: Some shifts toward circular economy practices, especially in agriculture and local craft industries.

The Bad: African consumption is already low—this SDG is effectively aimed at the West, but enforced in the South.

The Ugly: Africa is treated as a dump for used clothing, e-waste, and plastic, while also being blamed for overpopulation and told to “consume responsibly.”

SDG 13: Climate Action

The Good: Regional climate strategies, afforestation, and improved resilience to floods and droughts are active in some nations.

The Bad: Africa contributes only 3% to global CO₂ emissions but is expected to meet the same net zero standards that Germany and the UK now flout.

The Ugly: Fossil fuel exploration is blocked in Africa, but promoted in Norway, the US, and even post-Brexit Britain. Africans are urged to “go solar” by those flying in private jets to climate summits.

SDG 14: Life Below Water

The Good: Marine protected areas and anti-poaching drives are increasing. Some success against illegal fishing.

The Bad: Foreign vessels still overfish African waters under EU licences. Local fishers are criminalised for feeding their families.

The Ugly: Climate treaties now threaten African coastal economies with Western carbon offset schemes. Seaweed farms and “blue carbon” projects are imposed as substitutes for actual fisheries.

SDG 15: Life on Land

The Good: Wildlife preservation, reforestation, and land rehabilitation have seen gains, especially with community-led conservation.

The Bad: Green colonialism resurfaces through carbon markets, displacing pastoralists and farmers for carbon credits.

The Ugly: Land is seized in the name of “protecting the planet.” Western firms buy carbon offsets while Africans lose ancestral homes. Nature is commodified for ESG portfolios.

SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions

The Good: Anti-corruption frameworks and civil society organisations have gained modest influence. Peacekeeping operations have saved lives.

The Bad: Justice is slow, Western-funded NGOs often supplant national systems, and “strong institutions” are redefined as compliant ones.

The Ugly: Foreign donors pick winners and fund “democracy promotion” selectively. When African elections go the wrong way, the SDG missionaries go silent.

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

The Good: International cooperation remains necessary; sharing knowledge, tech, and capital has real potential.

The Bad: These partnerships are almost always asymmetrical—dictated by donor terms and priorities.

The Ugly: The language of “partnership” masks dependency. Africa is not an equal at the table—it is the subject of the discussion. The SDG logo sits on documents denying African nations fossil fuel loans, industry funding, or land sovereignty.

We do not reject development. We reject its monopoly. We reject a development that builds solar panels in Switzerland from minerals stolen in the Congo, only to tell the Congolese they cannot burn gas to light their homes. We reject a development that calls us partners while dictating our choices, that builds boreholes with one hand and extracts oil, copper, gold, and dignity with the other.

The SDGs were sold as salvation. What they became was a stick for beating the poor, a branding exercise for rich NGOs, and a conscience balm for corporations whose real goal is profit, not people.