A Minecraft Story for 6-8 year olds

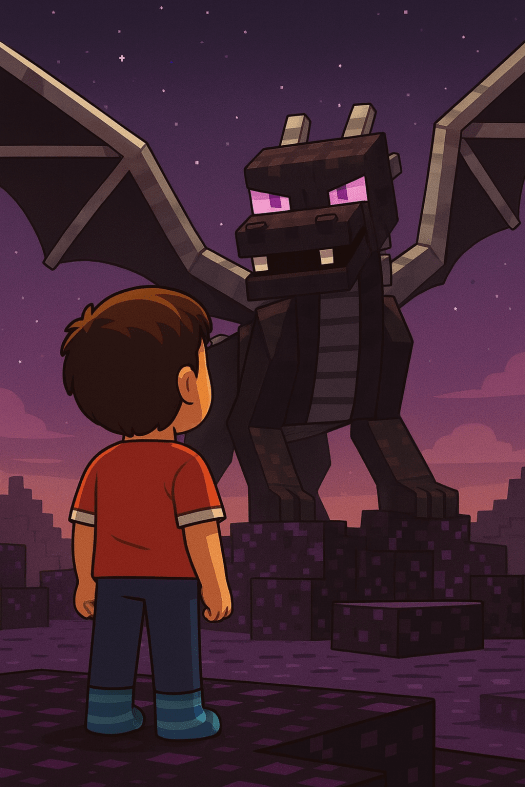

The Ender Dragon’s Secret

The End portal was already awake.

“That shouldn’t happen,” Alex said.

They stepped through.

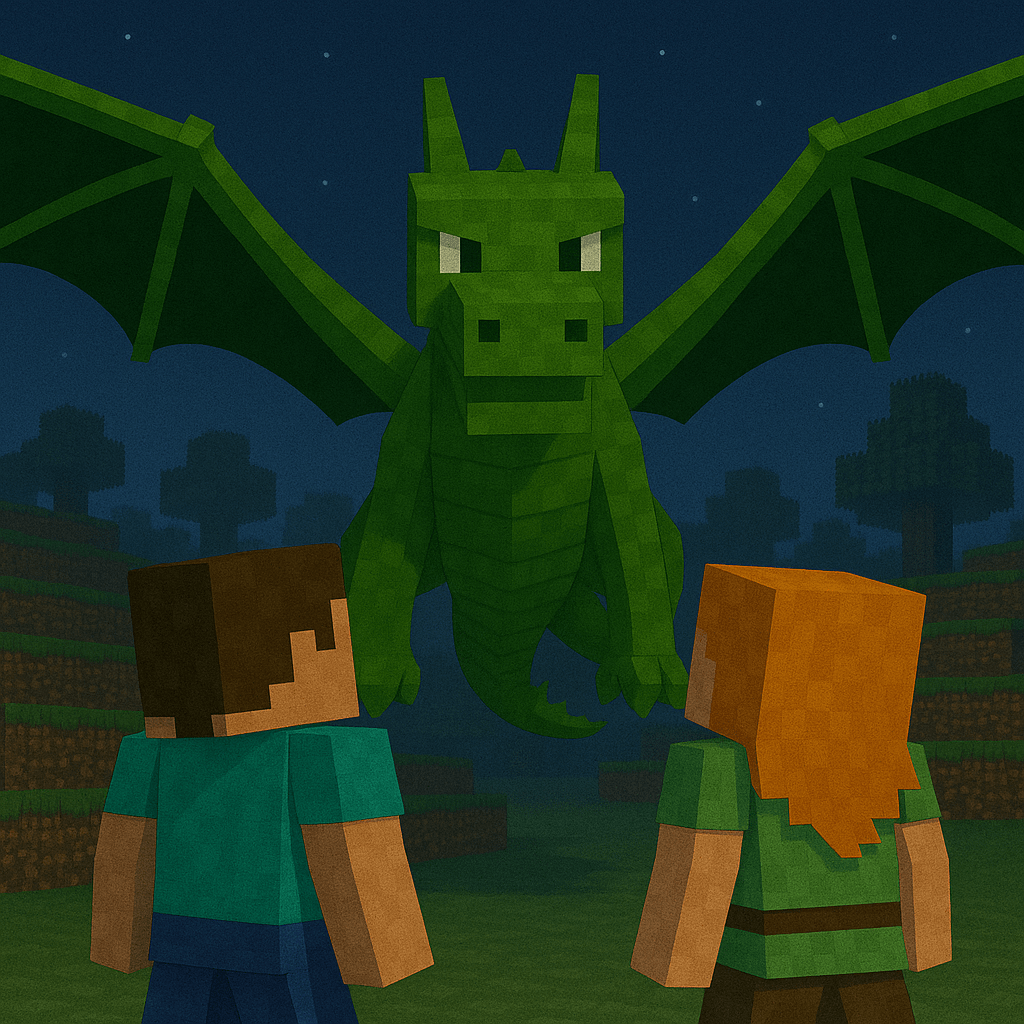

The End was quiet. The dragon circled high above, not attacking. Watching.

At the centre of the island, beneath cracked End Stone, they found an ancient lock — a stabiliser holding the world together.

The dragon landed between them and the structure. Not as an enemy. As a guardian.

Steve put his sword away. Alex did the same.

They spoke the words together, gently.

“Block by block.

Stone and wood.

Build it straight.

Build it good.”

The structure opened. They repaired it.

The cracks sealed. The End steadied.

The dragon bowed.

Some things, Steve realised, don’t need defeating.

Chris’s Story — The Frozen Builders

The village in the snow wasn’t broken.

It was paused.

Ice covered doors and wells, but nothing was damaged. Beneath the village, Steve and Alex found a cooling engine that had done its job too well.

“We don’t need to smash it,” Alex whispered.

They worked gently, one block at a time.

“Block by block.”

“Stone and wood.”

“Build it straight.”

“Build it good.”

The ice softened. The village woke quietly.

Steve thought of Chris — patient, careful, knowing when to stop.

Snow fell softly, just as it should.

Jonathan’s Story — The Jungle That Builds Back

The jungle copied everything.

Towers. Bridges. Clever tricks.

Each time Steve and Alex built, the temple rebuilt it stronger.

“It’s learning,” Alex said.

They stopped trying to be clever.

One block. Then another.

“Block by block.”

“Stone and wood.”

“Build it straight.”

“Build it good.”

The jungle slowed. The path opened.

Steve smiled. Jonathan would have understood — think ahead, build wisely.

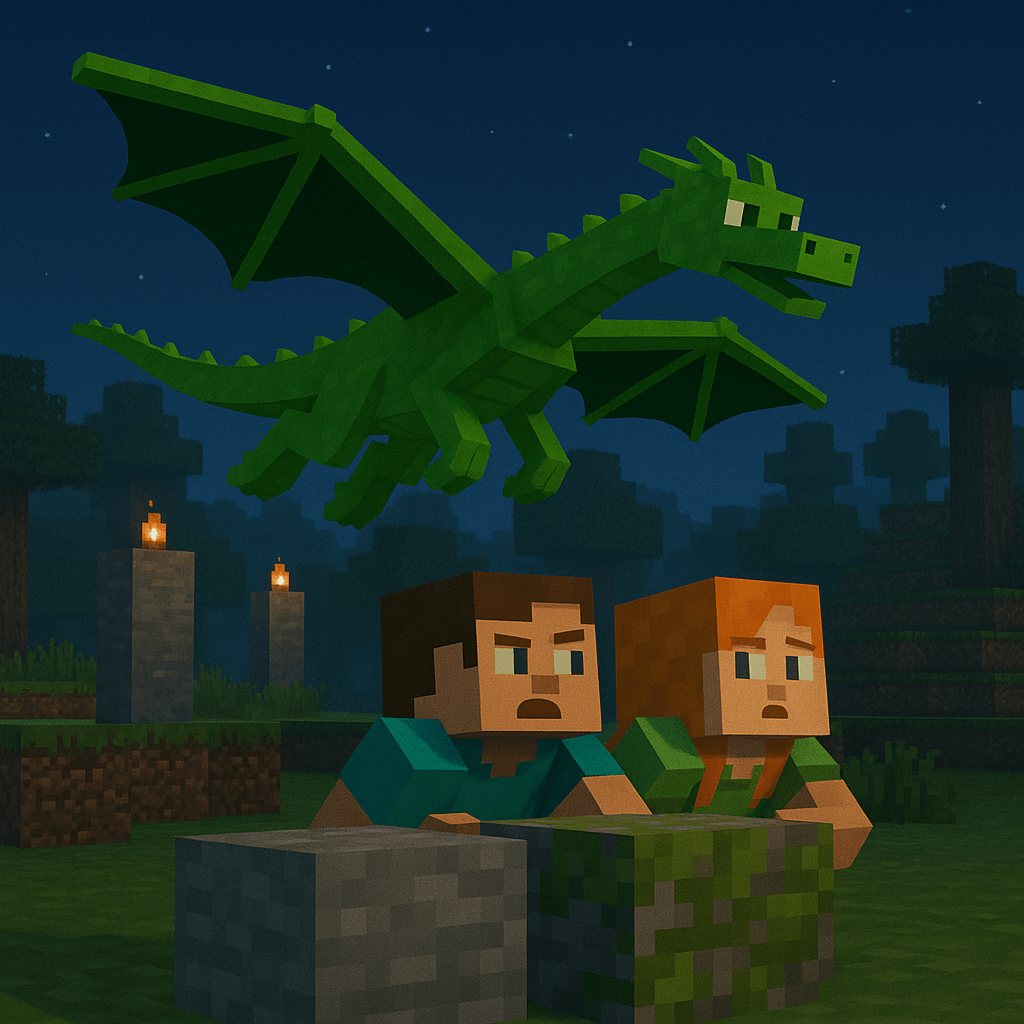

Epilogue — By the Campfire

That night, Steve and Alex sat by a campfire.

A map lay between them.

One mark in snow.

One in jungle green.

“The problems were different,” Alex said.

“But the answer wasn’t,” Steve replied.

They said the words one last time, quietly now — not a chant, just something true.

“Block by block.

Stone and wood.

Build it straight.

Build it good.”

The fire crackled.

The world rested.

And two builders slept, ready for tomorrow.