When Help Makes Things Worse

By Martyn Walker

Published in Letters from a Nation in Decline

Dear Reader,

There is a cruel illusion that stalks Western policymaking—an illusion we not only believe, but wrap in moral grandeur. It is the idea that if we lift a handful of people out of poverty, we have changed the world. A hundred million rescued, a headline for the BBC, a documentary narrated by Bono. Job done.

But what if this is the ultimate vanity project of the West? What if our relentless urge to “help” is a gilded form of sabotage?

Someone recently wrote online, with uncharacteristic clarity, that you could take 100 million people living in third-world poverty, move them to the United States, and still—still—billions would remain in that same poverty. The implication is hard to miss: the problem isn’t where the poor live. The problem is why poverty remains the dominant condition of those countries in the first place. And importing the poor to richer nations doesn’t solve the problem—it just relocates it and inflames a host of new ones.

We are encouraged to pity the migrants, not question the migration. Yet every one of those 100 million would cost billions to house, educate, subsidise, and absorb—while their departure does nothing to change the systems, cultures, or kleptocracies that bred their misery. Meanwhile, those left behind—numbering in the billions—are quietly erased from the ledger of Western concern.

And there is the sting: by rescuing the few, we abandon the many.

The road to this absurdity is paved with theological potholes and moral landmines. I recall the story of Pope John Paul II—beloved in the West for standing up to Soviet tyranny—visiting India during a time of desperate national struggle. The Indian government had, with considerable difficulty, built a network of family planning services, attempting to slow a spiralling birth rate in areas already plagued by malnutrition and drought. Charities worked hand in hand with officials to promote responsible contraception. It was not about ideology. It was about rice, water, and survival.

Then came the Pope.

With a few papal words, he condemned birth control in a country battling to feed its children. In an instant, years of careful groundwork were torched. His holiness departed in a plume of incense and rhetoric, leaving the consequences behind. He had the luxury of eternal principles. The people of India did not. The famine doesn’t care about doctrine.

This is what the West does best: it interferes. With speeches. With dogma. With chequebooks and conditions. And always, it leaves the bill with the locals.

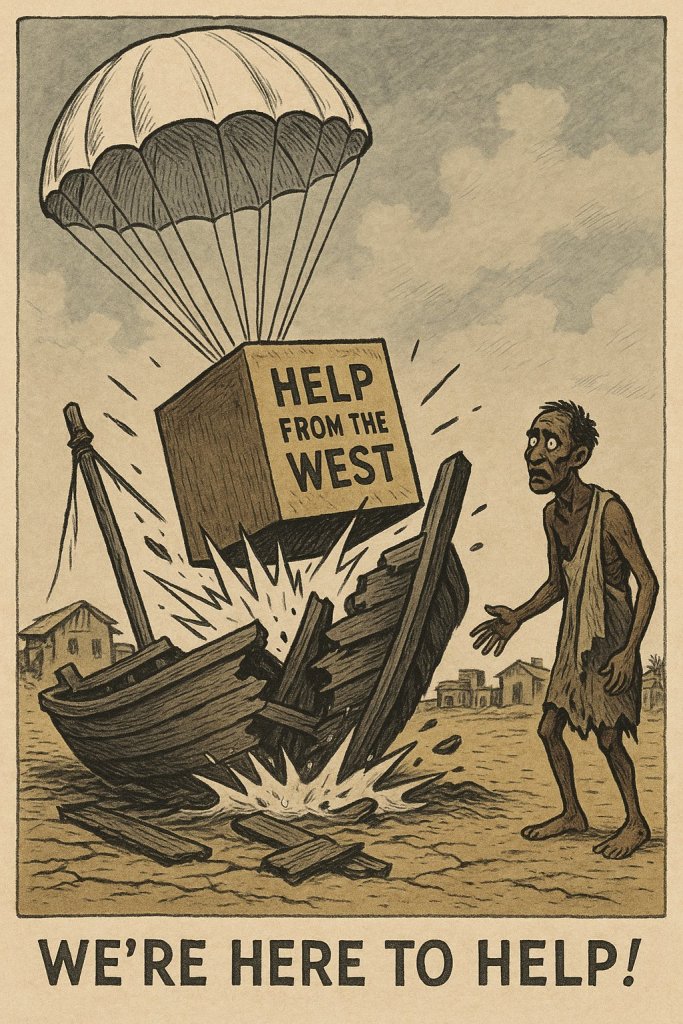

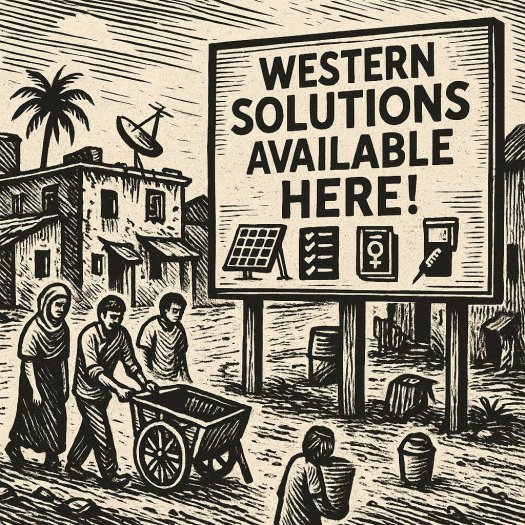

Let us speak plainly. The developing world does not suffer from a lack of Western help—it suffers from an excess of it. Help that creates dependency. Help that erodes initiative. Help that demands ideological obedience in return. We tie aid to carbon compliance, to gender theory, to imported bureaucracy. The IMF does not give loans—it issues control. The charities do not build capacity—they replace it.

We have reached a point where the so-called “help” from the West has become more dangerous than its absence. We call it development, but it resembles colonisation wearing a rainbow lanyard.

And when the help fails, we blame the locals for “corruption” as if the World Bank is a convent of saints. Or we propose the unthinkable: that a coalition of successful nations should once again assume managerial control of the “failing” ones. We are back to empire, except this time it’s run by NGOs and ESG consultants.

And if not that, we shrug—and let nature take its course.

So what, then? Do we retreat?

Yes, actually.

But not with malice. Not with neglect. With discipline. With humility. With the honest admission that teaching a man to fish is no good if we’ve already leased his lake to China, banned his nets under EU regulation, and filled the water with World Economic Forum pamphlets.

We must learn to get out of the way. Not walk away from the world, but stop trying to run it.

Give tools, not rules. Invest without conditions. Respect local agency. Stop importing problems into Western cities just to feel temporarily virtuous. And never again should we let theology—of any kind—override common sense in a starving country.

Let us finally admit it: we have become too proud of our pity, too in love with the mirror image of our benevolence. The poor do not need our rescue. They need their freedom—from us.

Faithfully yours,

M.W.

Letters from a Nation in Decline